Reason Observing Nature

Introduction

Let us briefly recall the nature of reason as it has so far developed. While its activity has become highly technical and nuanced, it is important not to lose sight of the formal essence of Reason, i.e. the necessary conditions that allow consciousness to be rational, the manner in which Reason undertakes rational and objective theorizing, and finally the final purpose and terminus for such an activity. We know Reason through the lens of the Aristotelian four causes, the four divine attributes of the universal substance which we have already touched upon. Reason is an expression of that knowable substance, and thus it is no surprise that Reason can be comprehended in terms of the four causes, while simultaneously comprehended in its own terms. Notice that self-consciousness does not unfold in line with linear history as we know it. There is nothing in the development thus far that would suggest that self-consciousness be limited to the temporal sequence which its physical and living bodies are subject. Indeed, Reason holds that time is not independent of conscious activity, but rather is itself an activity of self-consciousness. The movement of time is the movement of self-consciousness thinking itself, and in thinking itself elevating itself to higher and higher forms, incrementally growing in complexity from simplicity.

Recall the duplication of force into two distinct forces, reciprocally relating to each other. One is force expressed with force proper withdrawn into itself, the other is force proper with force express withdrawn into itself. The dual character of a single force, its expression as diverse matters and proper being as the thing-in-itself, was distributed between two forces. Force derived its mind-independent actuality by means of the duplication of force. Reason, certain of itself as the ultimate and essential universal substratum of all objective and subjective reality, takes this certitude for granted. The universally applicable, necessary, and schematized rules the transcendental unity of apperception ineluctibly obeys are distributed between the two distinct kinds of independent, self-same, realities - the self-differentiating unities of the the inner activity of consciousness and the objective flux of appearances. Just as force is defined as the interaction, i.e. the external relation, between two distinct and reciprocally related bodies, so too is Reason now defined as the interaction, i.e. the external relation, between two distinct and reciprocally related actualities.

Reason's taken for granted and instinctive certainty of its being the basis of all reality, inner and outer, at first was confined to the internal activity of the self - the only certain and rational truth is that I exist - whence the truth of the outer world of appearances was to be inferred, albiet unreliably. This internally self-related certainty has been dupicated and externalized. Thus, Reason expects to find the rationality inherent to the inner activity of self-conscious Reason in the external flux of appearances. The outer world, for Reason, is inherently rational. Reason duplicates its certainty of being all reality, and renders upon the external world of appearances the potential of being rationally accounted for. The two nodes, the source being the certainty of Reason, the sink being the inherent rationality of the objective world of appearances are established. The act of passive observation is the self-propelled motion of self-conscious Reason from the source to the sink. It is shaped like an electric/magnetic field.

The external world of appearanes is inherently rational, i.e. it is like self-conscious Reason, and can be known with the same universalizable, necessary, schematizable rules Reason uses to know itself, it is utterly bereaved of all self-conscious activity. This external world Reason calls Nature. In the Philosophy of Nature, Hegel writes:

"Nature has presented itself as the idea in the form of otherness. Since in nature the idea is as the negative of itself or is external to itself nature is not merely external in relation to this idea, but the externality constitutes the determination in which nature as nature exists. In this externality the determinations of the concept have the appearance of an indifferent subsistence and isolation in regards to each other. The concept therefore exists as an inward entity. Hence nature exhibits no freedom in its existence, but only necessity and contingency."

Living bodies, composed of organic matter, contain self-consciousness. Thus, Reason excludes organic matter from its passive observation. Determined to verify its own certitude of being the ultimate substrate of inner and outer reality by finding universally applicable and necessary rules that apply to both Nature and the activity of consciousness, Reason objectively observes inorganic nature.

Reason Observing Inorganic Nature

Self-conscious Reason is no longer a passive agent powerless to affect the content of its own development. Reason takes everything it has learned of itself in uncovering the universality implicit in the sense-data it receives from inorganic nature. While it is not capable of observing the total universality of the flux of appearances, it can account for the universal necessity and rationality of inorganic nature in which it receives its sense-data by means of universally applicable and necessary rules; the same rules that determine the movement self-consciousness. These rules, while they must circumscribe both the activity of self-conscious Reason and inorganic nature, must also not conflict with Reason's instinctive and taken for granted presumption that keeps the spheres of activity utterly distinct. The rules must keep the subjective and objective spheres of reality apart, but bring them together.

Nature exhibits both necessity, i.e. order, and contingency, i.e. chance. Universal necessity, what is also known as metaphysical necessity, is exhibited to Reason only when that necessary natural order is associated with universally applicable and necessary schematizing rules that equally apply to the activity of self-conscious Reason. Even though inorganic nature is bereaved of all conscious activity, it is still inherently rational, conformable to the rational activity of self-conscious Reason. Reason proclaims and demonstrates the reconciliation of the changeable and unchangeable, i.e. contingent and necessary, poles of the unhappy consciousness. The unhappy consciousness began its path towards reconciling its self-contradictory nature by means of devotion, surrendering its will to the universal. In seeking universal necessity in inorganic nature, self-conscious Reason does the same. The unhappy consciousness showed its devotion to itself as unchangeable by engaging in ritualized behaviour. This internal activity must be found in the external activity of inorganic nature, so Reason seeks the ritualized behaviour that inorganic nature exhibits.

The universal necessity of inorganic nature is to be sought first in the recurring patterns that inorganic nature exhibits. In observing the repetitions of sense-data that Reason receives through the senses and perception of its living body, Reason describes these regularities. The recurring patterns that Reason describes inhere in no specific object, but are rather abstractions it extracts from its observation of external reality. The recurring patterns it observes in inorganic nature occur, and found contingently as given. In order for the recurring pattern to be a universally applicable rule, Reason must find the necessity behind the recurring patterns it observes, on its own account, by chance contingently. Reason must find the reason behind recurring patterns. Inorganic nature is the set of all inorganic matter engaged in repeating motion, set into motion by another inorganic recurring pattern. This other inorganic recurring pattern was set into motion by yet another recurring pattern, ad infinitum.

No necessity can be established in the recurring patterns Reason contingently observes in inorganic nature. By definition, the motion of a universally necessary recurring pattern cannot be causally dependent on another recurring pattern. The recurring pattern has no objective universal significance on its own, but rather is given its universal significance by self-consciousness; the recurring pattern is universally significant only for self-consciousness. Reason does not just observe anything it senses and perceives, but only the sense-data that has a universal significance that is arbitrarily defined by self-consciousness - the ritualized behaviour of inorganic nature engaging in recurring patterns. The description of these patterns can apply to anything whatsoever. Reason cannot know whether it is objectively the describing the activity of inorganic nature, or whether it is projecting its own activity onto an inorganic nature which may in truth be pure contingency lacking any kind of necessity.

A nature of pure contingency is no nature at all, since it would lack any essential, self-same, and independent core. Without a universal substratum, nature cannot exist independently of the activity of self-conscious Reason. Conceding that nature is pure chance and contingency would undermine Reason's necessary assumption that the external world of inorganic nature is a self-same independent reality completely free of the creative activity of all self-conscious activity, sacred or profane. Reason realizes that the necessity of inorganic nature must exist on its own account, i.e. necessity is necessary.

On the other hand, Reason might be completely right in describing the entirety of inorganic nature in terms of recurring, mechanical, patterns. Here, nature is pure necessity, i.e. there exist no contingencies, everything is pre-determined. It would follow that the observations of Reason are also mechanistic and determined recurring patterns. The activity of self-conscious Reason would lack all independence from external reality. Divested of its own self-same independence, Reason would divest itself of the reconciliation between changeable and unchangeable that make the very activity of rational and objective observation possible. Its rationality would be irrational.

Thus, through observing recurring patterns in inorganic nature, Reason discovers the need for, yet cannot find a universally applicable and schematizable rule for establishing, the distinction between necessity and contingency in inorganic nature. Surrendering its will to the service of the universal produced the self-feeling of inner disruption for the unhappy consciousness. This dynamic recurs for Reason when it discovers that its description of recurring patterns accounts for the necessary aspects of inorganic nature contingently. The contingency of Reason's description are a direct product of self-conscious Reason's being confined to a contingent and particular living body - it cannot observe the totality of inorganic nature simultaneously. The universally applicable and schematizable rule that applies to self-conscious Reason is no longer the recurring patterns of its descriptions, but the individuality of self-conscious Reason reconciled with the unchangeable and universally significant self-certitude of Reason.

Reason now observes inorganic nature in accordance with a new universally applicable and schematizable rule that emphasizes the individuality of the sense-data it observes that nevertheless exists in relation to an objective universal. Reason, therefore, emphasizes the recurring appearances of certain properties that relate to a thing. Recall from perception that properties are individual sense-impressions that have a universal significance and make a thing determinate and perceivable, allowing us to distinguish between one thing and another. Reason, therefore, seeks those properties of an inorganic thing that have a universal significance - distinguishing marks.

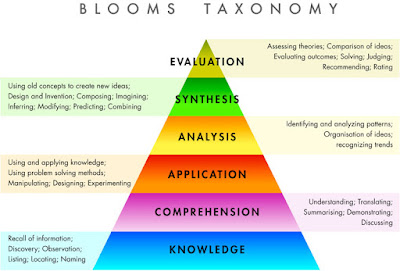

These distinguishing marks each have their own universal significance, with which Reason organizes inorganic matter and combines into groups and kinds in accordance to their commonly shared distinguishing marks. Reason engages in taxonomy.

The distinguishing marks of an individual denote the necessary, defining, substantial attribute of a thing - it is the thing's essential primary quality, which is a characteristic of a thing that exist in the thing itself independent of the activity of consciousness, and can be determined with certainty. Any other property, inessential secondary qualities, that belong to the thing can be attributed not to the thing itself, but to the activity of consciousness. Further, Reason relates each individual species of a thing to their own universality, a genus, in accordance to the primary qualities each kind of thing has in common. The recurring pattern has been reduced to finding bare similarities between one thing and another.

Reason distinguishes between essential objective properties of an inorganic substance and inessential subjective properties. The essential characteristics of a thing extend beyond the individual thing and make it a member of a class of things, a genus. Reason finds, however, that every class has an exception, as in, not all members of class A have quality B. The distinction that Reason has drawn between between essential and unessential is not in accordance to universally applicable and schematizable rule, as a recurring pattern or by engaging in taxonomy, but rather is arbitrary. The line it draws between essential and inessential is not necessarily inherent to the inorganic thing, since it finds that the thing itself does not distinguish itself from other things with the essential qualities Reason has assigned to it. The distinguishing mark that defines a thing, i.e. distinguishes that thing from other things, tends to vanish and become its opposite. It is not as stable as observing Reason first took it to be.

All properties are universal, and are thus related to infinity. Properties self-differentiate and become their own opposite. For example, the same matter that defines the solidity of a solid becomes the liquidity of a liquid. Force proper becomes force expressed, which in turn withdraws into itself and again becomes force proper, repeating this pattern ad infinitum. The world of appearances is in flux, self-differentiating. Reason identifies the notion of a stable and inert law that determinately describes the essential and necessary characteristic that defines objective inorganic nature - difference and change. The universally applicable and schematizable rule that Reason now turns to in order to establish a to circumscription between both the activity of self-conscious Reason and inorganic nature is a law that identifies simple difference in recurring patterns derived from the distinguishing marks of a thing.

What is necessary in inorganic nature becomes contingent, and what is contingent becomes necessary; what is essential becomes inessential, and what is inessential becomes essential. Reason attempts distinguishing between the necessary and unnecessary, essential and inessential, character of an inorganic thing by identifying its distinguishing marks, and associating the correlation between the inorganic thing and its distinguishing mark to a simple, self-distinguishing, lawlike universality, i.e. a number. Reason calculates probabilities and engages in making analogies between things and their distinguishing marks via mathematical functions.

The simple, lawlike, self-distinguishing while remaining in unity, character of numbers reflects the activity of self-consciousness as we continuously have seen. Reason identifies the distinguishing marks of an inorganic thing, and due to the self-distinguishing while remaining in unity character of a thing being reflected in numbers, so too do numbers reflect the activity of inorganic nature in flux. Numbers circumscribe both the activity of self-conscious Reason and the objective flux of inorganic nature. The laws of probability serve as the universally applicable and schematizable rules that bring the spheres of self-conscious activity and the flux of inorganic nature together, but keep them apart. Reason can even establish the rule that makes this kind of rulemaking essential and necessary: the flux of inorganic things, numbers, and self-conscious activity all share the same distinguishing mark of engaging in self-differentiation while remaining in unity - like becomes unlike, and unlike becomes like; law itself as inverted law makes law essential and necessary both for itself and for the recurring patterns it describes.

While having discovered the universalizing character of law and number, Reason can only make correlations between the distinguishing marks of a thing and its recurring appearance in relation to numerical probabilities, universals, with regards to what it has already observed in the past. Necessarily, the number of observations that Reason can make is finite, and every class of thing, even if they are brought together by laws of probability, has an exception. Thus, Reason associates the flux of inorganic matter to the inert stability of probabilistc laws with a degree of uncertainty.

The individual and particular living body of self-conscious Reason limits its capacity to make empirical observations. The activity of generating universal laws occurs within the strict confines of self-consciousness, which at some point in time must decay and die. These laws, already developed mathematically and ready for use, are imposed on the inorganic thing that may contingently possess the character of lawfulness. Probabilistic laws begin to develop in the activity of self-conscious Reason, and are applied to the empirical observations of the distinguishing marks of inorganic things post hoc.

The universal character of law inheres in its fluctuating tendency to differentiate itself from itself while remaining itself. As we saw in the section on understanding, a single law becomes a multiple collection of laws. Inorganic things are engaged in this same flux. The essential, necessary, and recurring distinguishing mark of an inorganic thing is its self-differentiating self-unity; a thing is a unity with many properties. Reason observes the thing with its essential and inessential properties. The inorganic thing is observed clothed in contingency, hiding the real, necessary, lawful, and essential distiguishing mark that underlies and defines it.

In order to grasp the essential and necessary character of the thing, Reason begins to unclothe the contingent qualities of a thing. An inorganic thing is related to itself, self-identical, self-differentiating by means of its own properties, which distinguish it from other inorganic things in its environment, which observing Reason also observes. The inorganic things that surround an inorganic thing are contigent. The essence of the thing is hidden by the contingent inorganic things that surround it. Reason modifies the environment in which the inorganic thing is immersed by setting up experiments in order to uncover the lawful nature of the inorganic thing.

Reason empirically observes and systematically keeps track of the character of the thing immersed in an environment that is continually purified of its extraneous, confounding, contingent character.

The particular kind sense-data available for empirical observation can be anything whatsover, since observation is the activity of a free and independent self-conscious Reason. In seeking to purify the inorganic thing of all contingency, Reason experiments on the inorganic thing, purifying it of all contingency by modifying the environment in which the inorganic thing is immersed to grasp its lawful essence. The pure lawful essence of the thing has no sensible or perceivable qualities; Reason grasps it only through numbers, ratios, formulae, and geometrical relationships.

The laws of probability were produced within the confines of a rational self-conscious activity, and correlated to the distinguishing marks of inorganic things that self-conscious Reason empirically observes. The physical laws of nature are derived from purifying the empirically existing inorganic thing of contingencies, confounding and extraneous contaminents from the environment in which the inorganic thing is immersed, including any property that allows self-conscious Reason to directly perceive and sense the inoganic thing. Both kinds of law, each with their own distinct origins whence they developed, are expressed by means of mathematical language, so Reason instinctively conflates the two kinds of law. From that strange conflation emerges the strange science, i.e. quantum physics. We shall say nothing more on it.

Now, laws like the Newton's Universal Law of Gravitation, Coulomb's Law, Maxwell's Equations allow self-conscious Reason to account for the recurring, essential, necessary, distinguishing marks of a thing, regardless of what contingent environment in which the inorganic thing may be immersed. Having discovered the lawful character of inorganic nature's structure and composition, holding that an inorganic thing derives its lawful character from its structure and composition, Reason has with certitude uncovered the unobservable but necessary and essential distinguishing mark of all inorganic things - matter, i.e. the unities involving protons, electrons, neutrons, the subatomic particles of an atomic nucleus, energy, etc. While these are no longer observable with the senses, nevertheless underly all things in empirical reality.

The matter which composes the thing in some kind of structural permutation necessarily and essentially determines the character of the inorganic thing regardless of what environment in which it is immersed, regardless of the contingent sensible and perceivable qualities a thing may possess. The properties of an atom depend on the number of protons in its nucleus. Reason has discovered the lawful character of the inorganic thing and purified it of all contingency, leaving only necessity. The inorganic thing, according to this inorganic purified law is immersed in its environment, and free and independent of the confounding character of the environment.

The self-differentiating unity of number integrates, but differentiates, the self-differentiating unity of the inorganic thing and self-conscious Reason. However, Reason cannot distinguish the moments of the purely conceptual dynamic just mentioned in the previous paragraph due to its stubborn and instinctive preference for empirical observation. Indeed, in order to fully establish the rationality of inorganic nature, Reason must conflate the three terms of the syllogism: number, inorganic activity, and conscious activity. Reason empirically observes a quantifiable thing that is immersed in its environment while being completely free and independent of it that is purely, and metaphysically, necessary for itself, i.e. the source of its own motion. Reason observes organic nature.

Reason Observing Organic Nature

Having conflated inorganic matter, number, and the activity of consciousness, Reason observes an object that combines all three of these qualities. Reason observes organic matter empirically, and the domain in which all organic matter subsists is organic nature. Organic nature, like inorganic nature, is bereaved of all self-conscious activity, yet Reason will again attempt to establish universally applicable and schematizable rules that circumscribe both the activity of self-conscious Reason and organic nature.

Reason treats organic matter no differently than inorganic matter, and thus, the same purified laws that Reason derived from the structure and composition of inorganic matter apply to organic matter. Like inorganic matter, organic matter is immersed in an environment composed of other organic matter as well as inorganic matter, yet is free and independent of it. The structure and composition of organic matter alone determines the schematic development of organic matter, undisturbed by the contaminating and confounding influence of the environment in which the organic matter is immersed. The nature of this development is best expressed by the morphology of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Self-conscious Reason, i.e. Goethe, observes the manner in which plants, composed of organic matter, develop.

The structure of the plant can be considered as a transforma-

tion of a single fundamental organ in accordance to internal laws of organization embedded in the self-same unity of the seed. Animals also develop in a similar manner to plants; one should take immediate notice that the development of self-consciousness up this point exactly follows the development of any kind of organic matter.

Reason discovers that the activity of consciousness is necessarily and essentially an organic activity, confined by the limits of a living body, immersed in an environment composed of organic and inorganic matter. Organic matter grows; the growth of an individual animal or plant depends for its preservation on nutrition; organic matter decays and dies; the preservation of a species depends on reproduction, asexual or sexual. Inorganic matter does not grow, develop, or reproduce in the same way that organic matter does. Thus, the scope of the universally applicable and schematizable laws that describe inorganic matter is too narrow to provide an objective, empirical, and rational account of the development, growth, and reproduction of organic matter. Self-conscious Reason must expand the scope of the universally applicable and schematizable purified law which it has found through experimentation. This expanded law must circumscribe the spheres of organic nature and inorganic nature, bringing them together but keeping them apart, it must account for the development and growth of organic nature; and in addition to circumscribing the two spheres of nature, it must circumscribe them and the activity of self-conscious Reason, keeping these three spheres together but keeping them apart.

Organic nature is held apart from inorganic nature, i.e. organic matter is immersed in an environment composed of inorganic and organic matter, yet is free and independent of it. For self-conscious Reason, the physical space occupied by an individual composed of organic matter, i.e. a cell, and the environment in which it is immersed are mutually exclusive. Each space operates in accordance to different laws. The mutual exclusivity between the two spaces is nevertheless a kind of relation, even if so far the relation has been conceived as an empty space where organic matter and the environment it is immersed in do not overlap. Self-conscious Reason, i.e Goethe, notices that the complete separation of the organism and its environment is an abstraction, writing that "the [organism] is formed by external conditions for external conditions." The environment does influence the development of the organism. The organism desires to consume organic matter immersed in the environment, without which the growth and development of the organism would not be possible.

That the organism is composed of organic and inorganic matter and is completely free of the environment is an abstraction which has its source in self-conscious Reason's conflation of number, inorganic matter, and self-conscious activity. The contingent conditions of the environment in which the organism, composed of organic and inorganic matter, is immersed have an influence on the development of the organism. The physical structure and composition of the organism, therefore, while it determines the schematic development of the organism in accordance to internal laws of organization present in the organism since its having been conceived through some kind of sexual union, nevertheless is dependent on the physical structure and composition of the environment in which it is immersed. The configuration of the environment is contigent, and being composed of inorganic matter, has recurring patterns and distinguishing marks. It has weather patterns, a climate, various kinds of inorganic matter of which the environment can be composed, which can be taxonomized into different kinds: rainforest, desert, tundra, parkland, oceans, rivers, air, etc.

What in my day has come to be called the theory of natural selection has retained the renown of a law of the same calibre of physical laws such as Newton's Universal Law of Gravitation. Newton's law states that all matter, by virtue of having mass, attracts other matter inversely proportional to the distance between to masses squared times a constant. Any mass, on any given planet, with any given planetary mass, will fall with a definite acceleration. The physical/chemical structure and composition of any kind of inorganic matter is determinately connected to the behaviour of that kind of inorganic matter. The theory of natural selection vaguely points on what kind of behaviour an organism tends towards, it cannot say with certitude what organism A will do at a point in space <x,y,z> at time t. In the same way Newton's mechanics describe with certitude the recurring patterns of aspects of inorganic nature, the theory of natural selection points out the recurring patterns of aspects of organic nature. There is no essential reason behind the recurring patterns natural selection, except the mindless, algorithmic, struggle for self-preservation and the propogation of an individual's genetic line. There is no necessity in the products of natural selection, but pure contingency. Even the emergence of the very self-conscious Reason that produced and made possible the emergence of the very theory of natural selection from a self-conscious activity is a contingency. Thus, any necessity that such a theory ascribes to itself is cancelled by the contingency it proudly takes credit for.

The schematic development of an organism in accordance to internal organization of the organism's genetic code, the very unit that justifies the veracity of natural selection, has an essential character to it. The genetic code contains the essential characteristics of the organism, determining which distinguishing marks the organism that develops therefrom shall exhibit. In seeking a law that circumscribes both the spheres of organic and inorganic nature, Reason now holds that the environment in which the organism is immersed also determines the distinguishing marks that the organism develops through adaptation and exhibits. The enivornment is identical to a gene. Montesquieu exhibits this idea when he writes in The Spirit of the Laws:

"Cold air constringes the extremities of the external fibres of the body; this increases their elasticity, and favours the return of the blood from the extreme parts to the heart. It contracts those very fibres; consequently it increases also their force. On the contrary, warm air relaxes and lengthens the extremes of the fibres; of course it diminishes their force and elasticity."

Cold air makes organisms strong, warm air weak. The very character of the organism is determined by the character of the environment. Tundra necessitates that the organism develop fur, the ocean necessitates that the organism develop fins, scales, and gills, the air necessitates that organisms develop feathers and wings, etc. By binding the distinguishing marks of an environment with the distinguishing marks of an organism, self-conscious Reason engages in developing two distinct taxonomies, one of the environment, the other of the organism, and combines them. This genetic binding of taxonomies has the appearance being a lawlike union, complete with deductions starting with the inorganic matter of the environment and ending with the organic matter of the organism, without actually being a law. That physical inorganic matter has mass and is separated from other inorganic matter by a distance necessitates gravitational pull, and vice versa. The presence of a north pole necessitates the presence of the south, and vice versa. The presence of positive charge necessitates the presence of negative, and vice versa. The presence of fur does not necessitate the presence of tundra; the presence of fins, gills, and scales do not necessitate the presence of ocean; the presence of wings does not necessitate the presence of air, etc. The organism is not bound to its environment in the same way that matter is bound to gravitational and electrical forces, but is free to migrate. No organism that migrates from its environment takes its environment with it; no furred animal migrating from the tundra to an environment with warmer climate takes the tundra with it.

The organism takes with it only the influence the environment has had on the development of its physical/chemical structure and composition. It is immersed in its environment, is influenced by it at a molecular and atomic level, but is not determined by it. The organism is free and independent of its environment, it is self-determining and engages in purposive activity linked to its own growth and development. This purposive activity is influenced by the environment it happens to be immersed in; although the environmental influence is not absolutely determining, it is constraining. The lack of water in a desert constrains the animal's desire to satisfy its thirst. The universally applicable rule and schematizable rule that circumscribes both organic and inorganic natures is no longer an absolutely determinative mechanistic physical law, but a teleology.

Inorganic matter, an inanimate substance, cannot provide a teleological purpose to the activity of an organism composed of organic matter, an animated subject. The environment composed of inorganic matter constrains the organism that develops, grows, is free to engage in the motion of its limbs while its body stays in one place and to engage in locomotion from one place to another within the same environment, or from one environment to another. Its motion follows specific rules, and is constrained by the geometric configuration of its limbs, i.e. the human forearm rotates about the elbow joint a maximum range of approximately 135° on a single plane from its fully expanded position. In order to engage in locomotion, the feet and arms of a human must oscillate like an alternating double pendulum, simultaneously producing enough force to keep the human body upright, as well as propel it forward with the help of the static friction force between the ground and the feet. To increase its speed, the human must lower the length of its limbs, pendulums, when running. Thus, it bends its arms and legs while swinging.

Locomotion methods are developed from the constraints an environment imposes on an organism; they are mechanistic and are bound by the mathematical and physical laws of inorganic nature. The organism teleomatically obeys rules that are external to it; rules that it neither chooses nor designs, nor comprehends without the most rudimentary capacity for intellect as it emerges in the understanding. In my day, the teleomatic constraints that inorganic matter imposes on organisms can be used to promote the growth and development of a specific kind of body, with a specific kind of structure and composition.

While engaging in motion and locomotion, the organism undergoes growth and development which requires nutrition. Regarding the human organism, Thomas Huxley writes:

"A living, active man constantly does mechanical work, gives off heat, evolves carbonic acid and water, and undergoes a loss of substance.

Plainly, this state of things could not continue for an unlimited period, or the man would dwindle to nothing. But long before the effects of this gradual diminution of substance become apparent to a bystander, they are felt by the subject of the experiment in the form of the two imperious sensations called hunger and thirst. To still these cravings, to restore the weight of the body to its former amount, to enable it to continue giving out heat, water, and carbonic acid, at the same rate, for an indefinite period, it is absolutely necessary that the body should be supplied with each of three things, and with three only. These are, firstly, fresh air; secondly, drink - consisting of water in some shape or other, however much it may be adulterated; thirdly food. That compound known to chemists as proteid matter, and which contains carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen, must form a part of this food, if it is to sustain life indefinitely; and fatty, starchy, or saccharine, i.e. carbohydrate matters, together with a certain amount of salts, ought to be contained in the food, if it is to sustain life conveniently."

The organism feels the absolute necessity of hydrating itself and keeping itself fed. It is internally driven by the imperatives of its living body to engage in rule governed procedural behaviour in order to fulfill an absolutely necessary purpose. The organism, as an activity of consciousness, neither chooses nor comprehends these drives. They are external to the organism, and are as immutable to it as are the mathematical and physical laws that deterministically govern nature. In engaging in purpose-driven behaviour, the organism acts teleonomically.

Teleological behaviour involves a purpose which an organism imposes on itself as a free and independent self-consciousness, where it sets goals for itself beyond engaging in mere nutrition and hydration, and engages in teleonomic purpose driven and teleomatic rule governed behaviour in order to satisfy said self-imposed goals. If the organism happens to be an estranged self-consciousness like the unhappy consciousness, its internal teleology appears to be an external teleology, where the organism as changeable sees itself as an artifact of a divine, unchangeable Creator. Self-conscious Reason, however, is not self-divided, but reconciled with itself. As an activity of self-consciousness, it sets a purpose for itself, and then acts via purpose-driven behaviour to actualize that self-imposed purpose.

The purpose which the organism sets for itself, as a free and independent self-consciousness, is predicated upon its freedom and independence as a self-conscious organism, i.e. the external environment does not determine for the organism what purpose it is to set for itself. The act of setting a purpose for oneself is, in other words, self-caused. It is motion where the organism causes itself to move in a kind of motion that may in accord with its own nature, or may be contrary to its own nature - the organism is free and independent of its environment; it may show itself to be free and independent of itself. Man may will himself to fly.

The organism sets a purpose for itself as an end, i.e. final cause. However, this end is not beyond the reach of the organism, but rather is present to it as soon as it sets this purpose for itself as a plan, i.e. formal cause. The end is present in the beginning. The beginning is an end that is not yet realized. The end, whether it is in accord to the present nature of the organism or not, is present as design. The organism is an artefact for itself, and engages in certain kinds of activity via purpose driven, rule-governed behaviour that will allow it to bring about and manifest its teleological purpose for itself.

This kind of activity is supposed to distinguish organic nature, inorganic nature, and self-conscious Reason, while circumscribing them. It is supposed to be universally applicable to all organisms, inorganic matter, and self-conscious Reason. It is supposed to be a necessary and schematizable activity. Thus, the end which the organism seeks must be universal.

But the organism is present to observation only as a particular individual organism. Reason cannot observe a universal individual. Any "universal" end that a particular individual sets for itself, an activity that is predicated on the individual's free and independent activity as an organism primarily concerned with its self-preservation, whether of itself qua individual via eating and drinking, or of itself qua member of a genus via sexual/asexual reproduction, turns out to be a particular end directed towards these things just mentioned. No organism can aspire towards a universal end that does not involve said organism.

The activity of an individual organism, to propagate itself as individual or member of a genus, begins and ends with the individual. This activity terminates once the life of the individual organism terminates. In the same way that the observation of recurring patterns in inorganic nature does not by itself show the reason behind those recurring patterns, so too does observing an organism engage in purposive activity not by itself show the reason behind that purposive activity.

To find the rationality behind the purposive activity of the organism, self-conscious Reason makes a distinction between its self-imposed internal purpose, and external purpose-driven, rule-governed behaviour which the organism must engage in due to the constraints of its environment in order to achieve this internal purpose. The self-imposed internal purpose of the organism is its intention, and the external purpose-driven behaviour that alters the living body of the organism and the environment that it is immersed in and constrains it is the consequence. Self-conscious Reason divides organic and inorganic, into inner and outer, and proclaims that the outer is the expression of the inner.

No comments:

Post a Comment